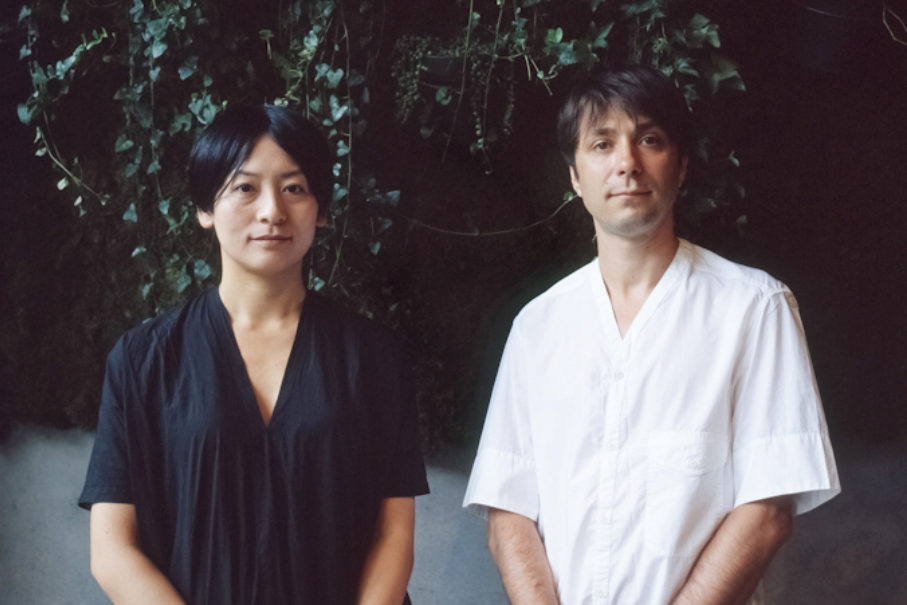

Hiroko Kusunoki and Nicolas Moreau

© Moreau KusunokiIn December 2019, Moreau Kusunoki won the international design competition to re-imagine the Powerhouse Parramatta museum, the largest investment in arts and culture in New South Wales, Australia, since the Sydney Opera House.

But this is not the French-Japanese studio’s first brush with success – in 2015, they won the highly competitive Guggenheim Helsinki Design Competition, beating over 1,700 other submissions.

MRC spoke to Hiroko Kusunoki and Nicolas Moreau to discover more about their approach to the competitive process and the impact competitions have upon their practice.

You’ve had great success with competitions so far – what’s the secret to a winning competition entry?

We’re very lucky to have been able to challenge the Guggenheim and Powerhouse competitions and be awarded the commissions. Their processes were quite different, but having a positive response to our scheme from the Jury made us so grateful.

We are not conscious of our secret to success, if we have one. The secret is probably already in the competition process itself – the gate was opened, so we took on the challenge. For us, a competition entry only has value if it manages to contribute something fresh, even if it is the smallest thing. We can measure that as a kind of ‘success’.

How does winning a competition impact your team?

Being recognised for the excellence of our work – that’s almost the only thing we would need to keep working with passion every day. It is very encouraging to know that the vision of the project we all shared internally is relatable to others, and it really justifies the effort and energy that we put into it. Our profession is linked with politics and economy, and open competitions offer a rare opportunity to ‘dream’ in a more shielded context.

Do you feel that competitions are now your practice’s speciality?

The majority of our work is actually won through competitions. Competitions are open invitations and they bring a breath of fresh air into our minds.

As we are not very active in media communications, a competition is a very limited occasion for us to express our thoughts through drawings. Only if we design a fair and honest proposal can we stimulate people’s attention and emotions, and engage them in our work.

What inspires you to enter a particular competition?

We pay particular attention to the members of the Jury. We believe that the selection of the Jury demonstrates the status of the project and is indicative of the relationship between the end users and the client.

How do you manage the competition process on a day-to-day level?

We try to keep developing several schemes, each of which needs to be very convincing on a certain aspect and idea, even if it does not reflect many of our other principles. The diversity of team members and backgrounds is crucial for this process.

Once we have defined the design direction that we will develop to the end, we try to challenge it internally, but also by inviting external advisors to provide their point of view.

How does designing for a competition differ from other projects?

Almost all of our projects have started from competitions, and we have limited experience with direct commissions to be able to compare.

One of the great values of competitions for us is the freedom. When working in a foreign context, competitors are not expected to master local conditions perfectly, but instead are encouraged to discover and challenge them positively. There is a distance to bridge between the end users and the participating architects, and we like the potential of this space. It helps us break out of our own clichés and think of others without preconceived ideas while shaping our architectural vision.

In that spirit, a good competition brief is not one that predetermines everything and deprives architects of such possibilities, but one that sets a framework while providing liberty. We consider ourselves fortunate to have worked with such briefs and been inspired by them.

What’s the most challenging part of entering a competition?

Being specific while remaining relative. Designing for today without becoming dated, and seeking intentional multiplicity of use rather than generic flexibility.

How do you deal with the disappointment of not winning?

We generally do not experience not winning as a disappointment. Winning or not should not fundamentally change our nature. Fortunately, we do not design a scheme only to win, but more to clarify our vision. And the result is very often a fruit of circumstances. Not winning also makes us challenge and revisit our ideas, which ultimately helps us to evolve and learn.

What advice would you offer other architects about the competition process?

Enjoy the process!

What’s the future for your practice?

We are still searching! It would be nice to find balance, in our life and our work, for us but also for our collaborators. On one hand, being aware of the small pleasures of everyday life; on the other hand, stretching our imagination far beyond. We like to play with this ambiguity, as it is our nature.